Showing posts with label The Byrds. Show all posts

Showing posts with label The Byrds. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Monday, September 3, 2007

The Byrds and I (Part Six)

The time has come for brand new entries in my Byrds and I series, in which I tell the story of my life through each album by my favorite band. Previous entries were...

1). Mr. Tambourine Man

2). Turn! Turn! Turn!

3). Fifth Dimension

4). Younger than Yesterday, Best of the Byrds Vol. 1 and Blur's Think Tank

5). The Notorious Byrd Brothers

Part Six: Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

Strike up a conversation with any music fan about the Byrds and Sweetheart will more than likely be the first record thar comes up. This is an odd and sometimes frustrating - it features just two original members and sounds nothing like any Byrds album that came before. Drummer Michael Clarke was replaced by Kevin Kelley, and Gram Parsons joined on guitar and vocals. Parsons stint with the band would only last a handful of months, but it dramatically changed their sound and left a very lasting impression. In fact, Parsons's contributions to the Byrds may be the most notable, second only to those of McGuinn.

Strike up a conversation with any music fan about the Byrds and Sweetheart will more than likely be the first record thar comes up. This is an odd and sometimes frustrating - it features just two original members and sounds nothing like any Byrds album that came before. Drummer Michael Clarke was replaced by Kevin Kelley, and Gram Parsons joined on guitar and vocals. Parsons stint with the band would only last a handful of months, but it dramatically changed their sound and left a very lasting impression. In fact, Parsons's contributions to the Byrds may be the most notable, second only to those of McGuinn.

Parsons's father committed suicide in 1958, when Gram was just 8 years old. His mother remarried and Gram would take the last name (Parsons) of his stepfather. His mother suffered from alcoholism and would eventually die of cirrhosis. Gram attended Harvard, studying theology, but left after just one semester. A small figure in the LA music scene, he would come to the attention of Byrd Chris Hillman, who wanted to take the group in a country/bluegrass direction. My dad had a song he would sing about Gram - "He was a man with a plan/country boy with a rock and roll band/Joined up with a band called the Byrds/and played country music like you never heard." The results of Sweetheart of the Rodeo would lay the foundation for what we think of today as alt-country.

"You Ain't Goin' Nowhere"

Parsons contributed several vocals to Sweetheart, however most would remain unheard for a number of years due to a contractual issue. A short while later, Parsons refused to play in South Africa, citing his opposition to apartheid, and was subsequently fired from the band. A year later, he would steal away Hillman to form the Flying Burrito Brothers and would continue to change the nature of country music. Parsons died of an overdose in 1973 in the Joshua Tree desert of Southern California.

My dad talked an awful lot about Parsons. He'd grown up in Fontana - not too far from that Southern California desert. He never went to college and described his high school years as somewhat troubled. After high school, he'd tell me of the pilgrimage he made to Joshua Tree to find Parsons. He said the first thing he ever told Gram was, "I thought your hair was longer," and he always felt stupid for having said that. He told me that the two bore a strong resemblance and if Gram was too drugged out to stand up for a Burrito Brothers photograph, my dad would stand in his place. I really have no idea whether these stories were true or not, but they felt pretty real as a ten year old.

Gram's "Hickory Wind" always makes me think of my dad - not the version on Sweetheart, but instead the live duet with Emmylou Harris on Grievous Angel. "In South Carolina, there're many tall pines," he sings, though I've never been to South Carolina and I can't imagine dad ever did either, but when the next line recalls, "I remember the oak tree that we used to climb," that makes me think about childhood. "But now when I'm lonesome I always pretend/That I'm gettin' the feel of hickory wind" ... I always loved that part.

I once asked my dad if he'd thought Parsons had committed suicide. My dad said he hadn't but that he knew what he was doing; that he knowingly was killing his body slowly over time. Again, I can't say whether my dad ever knew Parsons, but when I think about that statement now, and given how much my dad identified with Gram, it's pretty clear to me that he was talking about himself.

"Hickory Wind," Keith Richards

1). Mr. Tambourine Man

2). Turn! Turn! Turn!

3). Fifth Dimension

4). Younger than Yesterday, Best of the Byrds Vol. 1 and Blur's Think Tank

5). The Notorious Byrd Brothers

Part Six: Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

Strike up a conversation with any music fan about the Byrds and Sweetheart will more than likely be the first record thar comes up. This is an odd and sometimes frustrating - it features just two original members and sounds nothing like any Byrds album that came before. Drummer Michael Clarke was replaced by Kevin Kelley, and Gram Parsons joined on guitar and vocals. Parsons stint with the band would only last a handful of months, but it dramatically changed their sound and left a very lasting impression. In fact, Parsons's contributions to the Byrds may be the most notable, second only to those of McGuinn.

Strike up a conversation with any music fan about the Byrds and Sweetheart will more than likely be the first record thar comes up. This is an odd and sometimes frustrating - it features just two original members and sounds nothing like any Byrds album that came before. Drummer Michael Clarke was replaced by Kevin Kelley, and Gram Parsons joined on guitar and vocals. Parsons stint with the band would only last a handful of months, but it dramatically changed their sound and left a very lasting impression. In fact, Parsons's contributions to the Byrds may be the most notable, second only to those of McGuinn. Parsons's father committed suicide in 1958, when Gram was just 8 years old. His mother remarried and Gram would take the last name (Parsons) of his stepfather. His mother suffered from alcoholism and would eventually die of cirrhosis. Gram attended Harvard, studying theology, but left after just one semester. A small figure in the LA music scene, he would come to the attention of Byrd Chris Hillman, who wanted to take the group in a country/bluegrass direction. My dad had a song he would sing about Gram - "He was a man with a plan/country boy with a rock and roll band/Joined up with a band called the Byrds/and played country music like you never heard." The results of Sweetheart of the Rodeo would lay the foundation for what we think of today as alt-country.

"You Ain't Goin' Nowhere"

Parsons contributed several vocals to Sweetheart, however most would remain unheard for a number of years due to a contractual issue. A short while later, Parsons refused to play in South Africa, citing his opposition to apartheid, and was subsequently fired from the band. A year later, he would steal away Hillman to form the Flying Burrito Brothers and would continue to change the nature of country music. Parsons died of an overdose in 1973 in the Joshua Tree desert of Southern California.

My dad talked an awful lot about Parsons. He'd grown up in Fontana - not too far from that Southern California desert. He never went to college and described his high school years as somewhat troubled. After high school, he'd tell me of the pilgrimage he made to Joshua Tree to find Parsons. He said the first thing he ever told Gram was, "I thought your hair was longer," and he always felt stupid for having said that. He told me that the two bore a strong resemblance and if Gram was too drugged out to stand up for a Burrito Brothers photograph, my dad would stand in his place. I really have no idea whether these stories were true or not, but they felt pretty real as a ten year old.

Gram's "Hickory Wind" always makes me think of my dad - not the version on Sweetheart, but instead the live duet with Emmylou Harris on Grievous Angel. "In South Carolina, there're many tall pines," he sings, though I've never been to South Carolina and I can't imagine dad ever did either, but when the next line recalls, "I remember the oak tree that we used to climb," that makes me think about childhood. "But now when I'm lonesome I always pretend/That I'm gettin' the feel of hickory wind" ... I always loved that part.

I once asked my dad if he'd thought Parsons had committed suicide. My dad said he hadn't but that he knew what he was doing; that he knowingly was killing his body slowly over time. Again, I can't say whether my dad ever knew Parsons, but when I think about that statement now, and given how much my dad identified with Gram, it's pretty clear to me that he was talking about himself.

"Hickory Wind," Keith Richards

Friday, August 31, 2007

The Byrds and I (Part Five)

It has been some time since my last entry in the Byrds and I series, in which I tell the story of my life through each album by my favorite band. Previous entries were...

1). Mr. Tambourine Man

2). Turn! Turn! Turn!

3). Fifth Dimension

4). Younger than Yesterday, Best of the Byrds Vol. 1 and Blur's Think Tank

Part 5: The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1968)

The Notorious Byrd Brothers is not a record my dad and I ever listened to - yet I can recall its cover rather well. This cover shows the band now as a trio - McGuinn, Hillman and Clarke, with a horse supposedly to represent the ousted David Crosby. Crosby was a bit frustrated with the band's decision to use another Dylan cover as the lead single, as well as the fact that his tale of a three-way relationship, "Triad," was going to be left off. Tension was also brewing with Clarke, who would depart shortly after the album's release. Turmoil or not, however, the record is still considered one of their best, displaying the country influence that would overtake them later in the year. "Wasn't Born to Follow" is the song I can most vividly remember hearing, and I believe it would later play a prominent role in the film Easy Rider. "Draft Morning" I would later discover in the Steven Soderbergh film The Limey - the film that made me want to be a filmmaker. And such is the nature of the Byrds and myself - discovering them early in childhood, yet no matter how far I step away, they find their way back around to influence my life - sometimes only as background music.

The Notorious Byrd Brothers is not a record my dad and I ever listened to - yet I can recall its cover rather well. This cover shows the band now as a trio - McGuinn, Hillman and Clarke, with a horse supposedly to represent the ousted David Crosby. Crosby was a bit frustrated with the band's decision to use another Dylan cover as the lead single, as well as the fact that his tale of a three-way relationship, "Triad," was going to be left off. Tension was also brewing with Clarke, who would depart shortly after the album's release. Turmoil or not, however, the record is still considered one of their best, displaying the country influence that would overtake them later in the year. "Wasn't Born to Follow" is the song I can most vividly remember hearing, and I believe it would later play a prominent role in the film Easy Rider. "Draft Morning" I would later discover in the Steven Soderbergh film The Limey - the film that made me want to be a filmmaker. And such is the nature of the Byrds and myself - discovering them early in childhood, yet no matter how far I step away, they find their way back around to influence my life - sometimes only as background music.

"Wasn't Born to Follow" (this is not an "official" Byrds video, but you get to hear the song)

I was probably 17 when The Limey struck me. Sometime earlier, I watched Out of Sight - which has a very similar editing structure - and got my first taste of experimental cinema. Being rather unhappy, it was bits of experimentation in art in which I found solace. When I discovered Buffy the Vampire Slayer on the WB, I finally was able to see something that reflected what I was going through. Thus, Buffy and my brother Charlie's Little League games were about the only think I looked foreword to.

I was really bummed I missed Charlie's first home run. I had a physiology test which I badly needed to study for, though if I'd known I would have failed it anyway, I wouldn't have even bothered. I also missed the third by just a few seconds, but most importantly, I caught the second - and this I consider one of the single greatest moments of my entire life. You see, I was never quite good at baseball - much to my father's disappointment, and gave up by the time I was ten. Teaching Charlie how to play was important, and we spent many a night in the nearby park competing against one another. This relationship forged over baseball would later become the centerpiece of my college admissions essay, which detailed my close relationship with my brother. Sitting in the bleachers with the team's dads, I became Charlie's male representative - and thus received credit when something went his way. Thankfully, this was a rather frequent occurrence. I must have been 15 or 16, which would make Charlie 10 or 11, and I remember he was playing on the Royals. The Royals entered the final inning trailing significantly, and Charlie was not due to bat anytime soon. Yet, something happened and the team managed to bat the whole way around - bringing Charlie up with two outs and representing the winning run. Now my mom and I were nervous as hell as we huddled in the bleachers blowing air onto our cold hands - though I know Charlie was not.

Before Charlie hit the home run, I already knew it had happened. A second before his bat hit the ball, time actually froze. This is the only time that such a thing has happened for me, but gave me the chance to savor what was about to happen for just a little longer. When I recall it, the stopping of time is very vivid. And then it was over, and the expressions of joy from my mother and I were incredible. Now it is great that my brother hit a game-winning home run, but the event was more important for what it symbolized. For my brother and his quiet confidence; for my mother raising him and I alone; and for myself, seeing my brother accomplish something I never had, letting me know that he was going to be alright. My brother has since gone on to accomplish a number of things I never have - and it makes me happy every time.

1). Mr. Tambourine Man

2). Turn! Turn! Turn!

3). Fifth Dimension

4). Younger than Yesterday, Best of the Byrds Vol. 1 and Blur's Think Tank

Part 5: The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1968)

The Notorious Byrd Brothers is not a record my dad and I ever listened to - yet I can recall its cover rather well. This cover shows the band now as a trio - McGuinn, Hillman and Clarke, with a horse supposedly to represent the ousted David Crosby. Crosby was a bit frustrated with the band's decision to use another Dylan cover as the lead single, as well as the fact that his tale of a three-way relationship, "Triad," was going to be left off. Tension was also brewing with Clarke, who would depart shortly after the album's release. Turmoil or not, however, the record is still considered one of their best, displaying the country influence that would overtake them later in the year. "Wasn't Born to Follow" is the song I can most vividly remember hearing, and I believe it would later play a prominent role in the film Easy Rider. "Draft Morning" I would later discover in the Steven Soderbergh film The Limey - the film that made me want to be a filmmaker. And such is the nature of the Byrds and myself - discovering them early in childhood, yet no matter how far I step away, they find their way back around to influence my life - sometimes only as background music.

The Notorious Byrd Brothers is not a record my dad and I ever listened to - yet I can recall its cover rather well. This cover shows the band now as a trio - McGuinn, Hillman and Clarke, with a horse supposedly to represent the ousted David Crosby. Crosby was a bit frustrated with the band's decision to use another Dylan cover as the lead single, as well as the fact that his tale of a three-way relationship, "Triad," was going to be left off. Tension was also brewing with Clarke, who would depart shortly after the album's release. Turmoil or not, however, the record is still considered one of their best, displaying the country influence that would overtake them later in the year. "Wasn't Born to Follow" is the song I can most vividly remember hearing, and I believe it would later play a prominent role in the film Easy Rider. "Draft Morning" I would later discover in the Steven Soderbergh film The Limey - the film that made me want to be a filmmaker. And such is the nature of the Byrds and myself - discovering them early in childhood, yet no matter how far I step away, they find their way back around to influence my life - sometimes only as background music."Wasn't Born to Follow" (this is not an "official" Byrds video, but you get to hear the song)

I was probably 17 when The Limey struck me. Sometime earlier, I watched Out of Sight - which has a very similar editing structure - and got my first taste of experimental cinema. Being rather unhappy, it was bits of experimentation in art in which I found solace. When I discovered Buffy the Vampire Slayer on the WB, I finally was able to see something that reflected what I was going through. Thus, Buffy and my brother Charlie's Little League games were about the only think I looked foreword to.

I was really bummed I missed Charlie's first home run. I had a physiology test which I badly needed to study for, though if I'd known I would have failed it anyway, I wouldn't have even bothered. I also missed the third by just a few seconds, but most importantly, I caught the second - and this I consider one of the single greatest moments of my entire life. You see, I was never quite good at baseball - much to my father's disappointment, and gave up by the time I was ten. Teaching Charlie how to play was important, and we spent many a night in the nearby park competing against one another. This relationship forged over baseball would later become the centerpiece of my college admissions essay, which detailed my close relationship with my brother. Sitting in the bleachers with the team's dads, I became Charlie's male representative - and thus received credit when something went his way. Thankfully, this was a rather frequent occurrence. I must have been 15 or 16, which would make Charlie 10 or 11, and I remember he was playing on the Royals. The Royals entered the final inning trailing significantly, and Charlie was not due to bat anytime soon. Yet, something happened and the team managed to bat the whole way around - bringing Charlie up with two outs and representing the winning run. Now my mom and I were nervous as hell as we huddled in the bleachers blowing air onto our cold hands - though I know Charlie was not.

Before Charlie hit the home run, I already knew it had happened. A second before his bat hit the ball, time actually froze. This is the only time that such a thing has happened for me, but gave me the chance to savor what was about to happen for just a little longer. When I recall it, the stopping of time is very vivid. And then it was over, and the expressions of joy from my mother and I were incredible. Now it is great that my brother hit a game-winning home run, but the event was more important for what it symbolized. For my brother and his quiet confidence; for my mother raising him and I alone; and for myself, seeing my brother accomplish something I never had, letting me know that he was going to be alright. My brother has since gone on to accomplish a number of things I never have - and it makes me happy every time.

Tuesday, August 28, 2007

The Byrds and I (Part Two)

The Byrds and I is a series of essays chronicling the story of my life through each album from my favorite band. Previously, I wrapped my thoughts around 1965's Mr. Tambourine Man.

Part Two: Turn Turn Turn (1965)

Re-reading what I've thus far written and hoped to pass off as part two of this series, I can't help but feel a little bit unsatisfied with what I've put down. It feels a bit unfocused to me - but at the same time I think it reflects a very honest portrayl of what my writing used to read like. I actually haven't tackled such a writing assignment in some time, so as this series of essays procedes, I may have to again go through that fine artistic task of finding one's voice. Consider this a transitional piece, in which I will present many ideas that will be developed more profoundly later on. That is rather fitting because Turn!Turn!Turn! does pretty much the same thing - at least that's how I like to look at it.

Re-reading what I've thus far written and hoped to pass off as part two of this series, I can't help but feel a little bit unsatisfied with what I've put down. It feels a bit unfocused to me - but at the same time I think it reflects a very honest portrayl of what my writing used to read like. I actually haven't tackled such a writing assignment in some time, so as this series of essays procedes, I may have to again go through that fine artistic task of finding one's voice. Consider this a transitional piece, in which I will present many ideas that will be developed more profoundly later on. That is rather fitting because Turn!Turn!Turn! does pretty much the same thing - at least that's how I like to look at it.

Released just months of Mr. Tambourine Man, Turn!Turn!Turn came at the height of the band's "America's Answer to the Beatles" status. It would be their last genuine folk rock effort and while not predicting the psychedelic direction the band would soon take, it did nicely close the first chapter of the band's history. They finally mastered "It Won't Be Wrong," a tune that had been developing since their earliest sessions, eventually becoming a jangly love song with two distinct yet complimentary parts. The chorus, one could argue, hinted at the alt-country the band would pioneer years later. McGuin truly came into his own as a songwriter with his JFK-eulogy, "He Was a Friend of Mine." Perhaps he was unsatisfied with the initial results, though, as it would later be re-recorded by two different formations of the band. There's a rather perplexing cover of "Oh! Suzanna," but as stated before, McGuin was interested in all kinds of music and had no pretense about covering a folk song of any nature or origin. In fact, his work today consists primarily of sharing traditional folk songs with internet listeners. Of course, the band was still re-working Dylan and attempted to rock out both "The Times They Are A'Changin'" and "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue." Only the latter made the cut, as "Baby Blue" would not show up until McGuin was the last Byrd standing.

Of course, it was in covering Pete Seeger - not Dylan - that the Byrds managed to find their defining moment. Unlike the "Tambourine Man" cover which seemed to strip the meaning of the original in place of pop catchiness, the pop-like nature of "Turn Turn Turn" actually seemed to make the song more meaningful. Lyrically, such biblical words have never managed to move me, except when coming from the mouths of the four part harmony. With each line met with a "Turn Turn Turn" they sing, "to everything/ there is a season/ and a time for every purpose/ under heaven/ a time." They continue, "A time to be born, a time to die, time to plant, a time to reap, a time to, kill, a time to heal, A time to laugh, a time to weep," and, really, more honest words were probably never spoken. Though I don't consider myself a religious person in any sense, I can't help but find peace in the song's philosophy. It didn't quite resonate with me in such a way initially, but after hearing it at a funeral years later, it's doubtful I will ever forget that melody. If it sounds at all familiar, I'm guessing you recall it from The Wonder Years, which seems to establish the fact that something in the song's opening triggers a rather universal emotion.

Of course, it was in covering Pete Seeger - not Dylan - that the Byrds managed to find their defining moment. Unlike the "Tambourine Man" cover which seemed to strip the meaning of the original in place of pop catchiness, the pop-like nature of "Turn Turn Turn" actually seemed to make the song more meaningful. Lyrically, such biblical words have never managed to move me, except when coming from the mouths of the four part harmony. With each line met with a "Turn Turn Turn" they sing, "to everything/ there is a season/ and a time for every purpose/ under heaven/ a time." They continue, "A time to be born, a time to die, time to plant, a time to reap, a time to, kill, a time to heal, A time to laugh, a time to weep," and, really, more honest words were probably never spoken. Though I don't consider myself a religious person in any sense, I can't help but find peace in the song's philosophy. It didn't quite resonate with me in such a way initially, but after hearing it at a funeral years later, it's doubtful I will ever forget that melody. If it sounds at all familiar, I'm guessing you recall it from The Wonder Years, which seems to establish the fact that something in the song's opening triggers a rather universal emotion.

Of course, "The Wonder Years Effect" seems to drum up notions of of nostalgia, and sentimentality, two things lacking from how I look at my childhood. In fact the Byrds weren't quite my soundtrack, but instead, my release. Getting lost in their records and learning every detail of their history was a nice distraction from the confusion that seemed to fill my hours before I would get home to the safety of my cd player. Explaining this will take some time, but I think it's best to start by introducing some of the defining factors in my life. My brother Charlie was born five years after me and though not initially a music nut such as myself, he's certainly developed into a full-fledged one now. I can't help but want to take a little credit for that, seeing as how - when it came to my brother - I always wanted to lead by example. At the core, our relationship has always been strong but each of us has been prone to become very annoyed with the other on numerous occasions. When our parents got divorced, I was ten and he was five. My father moved out, and while he stayed in the picture, the three of us often felt as though we were all we had. My mother first worked in my elementary school library before eventually settling as a manager at a bookstore, while I spent a great deal of time keeping an eye on my brother. This was fine by me, as the bond we formed quickly proved much more important than the frivolous activities associated with a teenage social life. In fact, as I taught my brother how to play baseball and introduced him to my various interests, I'm came to feel as if I was fulfilling the positive older male roll.

Of course, in my ability to grow up very quickly, I lost sense of what it actually meant to grow up, and while I felt confident in what I believed to be wisdom beyond my years, I also felt completely lost. I then retreated into the wonders of my own head, a space where bad song lyrics and pretty decent television plots fostered and grew. It wasn't until years later that I actually got to see them realized in a visual sense, but looking back, I am rather grateful to have had so much time alone with my thoughts. I highly doubt I'd be who I am now without that.

Part Two: Turn Turn Turn (1965)

Re-reading what I've thus far written and hoped to pass off as part two of this series, I can't help but feel a little bit unsatisfied with what I've put down. It feels a bit unfocused to me - but at the same time I think it reflects a very honest portrayl of what my writing used to read like. I actually haven't tackled such a writing assignment in some time, so as this series of essays procedes, I may have to again go through that fine artistic task of finding one's voice. Consider this a transitional piece, in which I will present many ideas that will be developed more profoundly later on. That is rather fitting because Turn!Turn!Turn! does pretty much the same thing - at least that's how I like to look at it.

Re-reading what I've thus far written and hoped to pass off as part two of this series, I can't help but feel a little bit unsatisfied with what I've put down. It feels a bit unfocused to me - but at the same time I think it reflects a very honest portrayl of what my writing used to read like. I actually haven't tackled such a writing assignment in some time, so as this series of essays procedes, I may have to again go through that fine artistic task of finding one's voice. Consider this a transitional piece, in which I will present many ideas that will be developed more profoundly later on. That is rather fitting because Turn!Turn!Turn! does pretty much the same thing - at least that's how I like to look at it.Released just months of Mr. Tambourine Man, Turn!Turn!Turn came at the height of the band's "America's Answer to the Beatles" status. It would be their last genuine folk rock effort and while not predicting the psychedelic direction the band would soon take, it did nicely close the first chapter of the band's history. They finally mastered "It Won't Be Wrong," a tune that had been developing since their earliest sessions, eventually becoming a jangly love song with two distinct yet complimentary parts. The chorus, one could argue, hinted at the alt-country the band would pioneer years later. McGuin truly came into his own as a songwriter with his JFK-eulogy, "He Was a Friend of Mine." Perhaps he was unsatisfied with the initial results, though, as it would later be re-recorded by two different formations of the band. There's a rather perplexing cover of "Oh! Suzanna," but as stated before, McGuin was interested in all kinds of music and had no pretense about covering a folk song of any nature or origin. In fact, his work today consists primarily of sharing traditional folk songs with internet listeners. Of course, the band was still re-working Dylan and attempted to rock out both "The Times They Are A'Changin'" and "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue." Only the latter made the cut, as "Baby Blue" would not show up until McGuin was the last Byrd standing.

Of course, it was in covering Pete Seeger - not Dylan - that the Byrds managed to find their defining moment. Unlike the "Tambourine Man" cover which seemed to strip the meaning of the original in place of pop catchiness, the pop-like nature of "Turn Turn Turn" actually seemed to make the song more meaningful. Lyrically, such biblical words have never managed to move me, except when coming from the mouths of the four part harmony. With each line met with a "Turn Turn Turn" they sing, "to everything/ there is a season/ and a time for every purpose/ under heaven/ a time." They continue, "A time to be born, a time to die, time to plant, a time to reap, a time to, kill, a time to heal, A time to laugh, a time to weep," and, really, more honest words were probably never spoken. Though I don't consider myself a religious person in any sense, I can't help but find peace in the song's philosophy. It didn't quite resonate with me in such a way initially, but after hearing it at a funeral years later, it's doubtful I will ever forget that melody. If it sounds at all familiar, I'm guessing you recall it from The Wonder Years, which seems to establish the fact that something in the song's opening triggers a rather universal emotion.

Of course, it was in covering Pete Seeger - not Dylan - that the Byrds managed to find their defining moment. Unlike the "Tambourine Man" cover which seemed to strip the meaning of the original in place of pop catchiness, the pop-like nature of "Turn Turn Turn" actually seemed to make the song more meaningful. Lyrically, such biblical words have never managed to move me, except when coming from the mouths of the four part harmony. With each line met with a "Turn Turn Turn" they sing, "to everything/ there is a season/ and a time for every purpose/ under heaven/ a time." They continue, "A time to be born, a time to die, time to plant, a time to reap, a time to, kill, a time to heal, A time to laugh, a time to weep," and, really, more honest words were probably never spoken. Though I don't consider myself a religious person in any sense, I can't help but find peace in the song's philosophy. It didn't quite resonate with me in such a way initially, but after hearing it at a funeral years later, it's doubtful I will ever forget that melody. If it sounds at all familiar, I'm guessing you recall it from The Wonder Years, which seems to establish the fact that something in the song's opening triggers a rather universal emotion.Of course, "The Wonder Years Effect" seems to drum up notions of of nostalgia, and sentimentality, two things lacking from how I look at my childhood. In fact the Byrds weren't quite my soundtrack, but instead, my release. Getting lost in their records and learning every detail of their history was a nice distraction from the confusion that seemed to fill my hours before I would get home to the safety of my cd player. Explaining this will take some time, but I think it's best to start by introducing some of the defining factors in my life. My brother Charlie was born five years after me and though not initially a music nut such as myself, he's certainly developed into a full-fledged one now. I can't help but want to take a little credit for that, seeing as how - when it came to my brother - I always wanted to lead by example. At the core, our relationship has always been strong but each of us has been prone to become very annoyed with the other on numerous occasions. When our parents got divorced, I was ten and he was five. My father moved out, and while he stayed in the picture, the three of us often felt as though we were all we had. My mother first worked in my elementary school library before eventually settling as a manager at a bookstore, while I spent a great deal of time keeping an eye on my brother. This was fine by me, as the bond we formed quickly proved much more important than the frivolous activities associated with a teenage social life. In fact, as I taught my brother how to play baseball and introduced him to my various interests, I'm came to feel as if I was fulfilling the positive older male roll.

Of course, in my ability to grow up very quickly, I lost sense of what it actually meant to grow up, and while I felt confident in what I believed to be wisdom beyond my years, I also felt completely lost. I then retreated into the wonders of my own head, a space where bad song lyrics and pretty decent television plots fostered and grew. It wasn't until years later that I actually got to see them realized in a visual sense, but looking back, I am rather grateful to have had so much time alone with my thoughts. I highly doubt I'd be who I am now without that.

Monday, August 27, 2007

The Byrds and I (Part One)

The Byrds and I is a series chronicling the story of my life through each album by my favorite band.

Part One: Mr. Tambourine Man (1965)

To anyone who reads this blog on a regular basis, or to anyone who knows me personally, my love and passion for music is very apparent. While this has grown into obsession in recent years, this passion is something that I've carried with me for almost as long as I can remember. My father is the one to blame, as his record collection - honed over decades then reconstructed after an unfortunate theft - served as my own personal school of rock. I'm told I wouldn't go to sleep unless rocked to the sounds of Graham Parker or Roxy Music, and when I reached such an age of curiosity, I found myself pulling out albums at random, anxious for the stories they held. Stories were not lacking when I came to records in my father's collection, and like most young boys who idolize their dads, his favorites became my favorites. John Lennon, Bob Dylan and American five piece, the Byrds, became the most important thing in the world to me at that point. I was probably 8 or 9, and I can't say I was much of a happy child. I had great difficulty focusing in school - result of a learning disability that lead teachers and students to question my level of intelligence. Needless to say, friends weren't easy to come by either, and the best part of my day became being able to indulge in the sounds of a decade I so badly wished to be a part of.

To anyone who reads this blog on a regular basis, or to anyone who knows me personally, my love and passion for music is very apparent. While this has grown into obsession in recent years, this passion is something that I've carried with me for almost as long as I can remember. My father is the one to blame, as his record collection - honed over decades then reconstructed after an unfortunate theft - served as my own personal school of rock. I'm told I wouldn't go to sleep unless rocked to the sounds of Graham Parker or Roxy Music, and when I reached such an age of curiosity, I found myself pulling out albums at random, anxious for the stories they held. Stories were not lacking when I came to records in my father's collection, and like most young boys who idolize their dads, his favorites became my favorites. John Lennon, Bob Dylan and American five piece, the Byrds, became the most important thing in the world to me at that point. I was probably 8 or 9, and I can't say I was much of a happy child. I had great difficulty focusing in school - result of a learning disability that lead teachers and students to question my level of intelligence. Needless to say, friends weren't easy to come by either, and the best part of my day became being able to indulge in the sounds of a decade I so badly wished to be a part of.

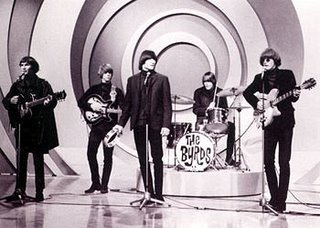

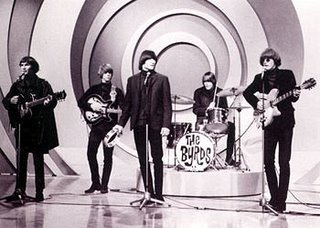

The Byrds hit the American airwaves in 1965, as rock and roll began to divert from basic rhythm and blues to more experimental sounds, and dissenting voices began to emerge against the actions of the government. Dylan proved to be the voice of a generation, yet his folksy political wisdom didn't quite exactly translate into pop success. Byrds frontman Jim McGuin was interested in all kinds of music, but his initial inkling was to blend that folk wisdom with the pop tightness of the Beatles - creating a sound that was catchy, yet anthemic. Mr. Tambourine Man is full of Dylan covers, with the title track becoming their first number one. Dylan's "Tambourine Man" clocked in at over six minutes, but McGuin chopped it to under two, rendering the song radio friendly, if somewhat meaningless. Elsewhere it was the tight harmonies of McGuin, David Crosby, Gene Clark and Chris Hillman that would ultimately characterize the Byrds' sound. Drummer Michael Clarke did not spend too much time on the microphone.

I would discover gems much later - because I don't actually think I made it too far past the first two songs. After "Tambourine Man" came one of Gene Clark's originals, "I'll Feel A Whole Lot Better." Clark was my dad's favorite Byrd - at least until Gram Parsons joined. My dad always identified with the underdog - often a tragic underdog. Clark would only record one other album with the band, before embarking on a solo career that only saw success and acclaim after his passing. Clark was a great songwriter and - not playing an instrument himself - was the one who held the harmonies in the line.

Decades later, my favorites on this album are originals buried deep beneath the covers. I care little for their rendition of the title track when stacking it up against the others, and it is Dylan's original that holds resonance. My mom always preferred that version, most notably the line, "to dance beneath the diamond skies with one hand waving free." In 2003, I was working on a documentary film about my mom's brother, Steve, who'd committed suicide years before I was born. Her family had grown up in Michigan, but Steve had come to San Francisco in the sixties searching for something. As we strolled Haight Street and I filmed the scenery, we happened upon a street performer. I chatted with him briefly and he informed me that he played mostly Dylan songs. I asked him if I could film him playing his favorite. He agreed, and proceeded to sing "Mr. Tambourine Man." Though it was all by chance, that moment ended up becoming a defining point in the film. Even if I tried to escape them, the music that defined my life as a child continues to define it today.

Part One: Mr. Tambourine Man (1965)

To anyone who reads this blog on a regular basis, or to anyone who knows me personally, my love and passion for music is very apparent. While this has grown into obsession in recent years, this passion is something that I've carried with me for almost as long as I can remember. My father is the one to blame, as his record collection - honed over decades then reconstructed after an unfortunate theft - served as my own personal school of rock. I'm told I wouldn't go to sleep unless rocked to the sounds of Graham Parker or Roxy Music, and when I reached such an age of curiosity, I found myself pulling out albums at random, anxious for the stories they held. Stories were not lacking when I came to records in my father's collection, and like most young boys who idolize their dads, his favorites became my favorites. John Lennon, Bob Dylan and American five piece, the Byrds, became the most important thing in the world to me at that point. I was probably 8 or 9, and I can't say I was much of a happy child. I had great difficulty focusing in school - result of a learning disability that lead teachers and students to question my level of intelligence. Needless to say, friends weren't easy to come by either, and the best part of my day became being able to indulge in the sounds of a decade I so badly wished to be a part of.

To anyone who reads this blog on a regular basis, or to anyone who knows me personally, my love and passion for music is very apparent. While this has grown into obsession in recent years, this passion is something that I've carried with me for almost as long as I can remember. My father is the one to blame, as his record collection - honed over decades then reconstructed after an unfortunate theft - served as my own personal school of rock. I'm told I wouldn't go to sleep unless rocked to the sounds of Graham Parker or Roxy Music, and when I reached such an age of curiosity, I found myself pulling out albums at random, anxious for the stories they held. Stories were not lacking when I came to records in my father's collection, and like most young boys who idolize their dads, his favorites became my favorites. John Lennon, Bob Dylan and American five piece, the Byrds, became the most important thing in the world to me at that point. I was probably 8 or 9, and I can't say I was much of a happy child. I had great difficulty focusing in school - result of a learning disability that lead teachers and students to question my level of intelligence. Needless to say, friends weren't easy to come by either, and the best part of my day became being able to indulge in the sounds of a decade I so badly wished to be a part of.The Byrds hit the American airwaves in 1965, as rock and roll began to divert from basic rhythm and blues to more experimental sounds, and dissenting voices began to emerge against the actions of the government. Dylan proved to be the voice of a generation, yet his folksy political wisdom didn't quite exactly translate into pop success. Byrds frontman Jim McGuin was interested in all kinds of music, but his initial inkling was to blend that folk wisdom with the pop tightness of the Beatles - creating a sound that was catchy, yet anthemic. Mr. Tambourine Man is full of Dylan covers, with the title track becoming their first number one. Dylan's "Tambourine Man" clocked in at over six minutes, but McGuin chopped it to under two, rendering the song radio friendly, if somewhat meaningless. Elsewhere it was the tight harmonies of McGuin, David Crosby, Gene Clark and Chris Hillman that would ultimately characterize the Byrds' sound. Drummer Michael Clarke did not spend too much time on the microphone.

I would discover gems much later - because I don't actually think I made it too far past the first two songs. After "Tambourine Man" came one of Gene Clark's originals, "I'll Feel A Whole Lot Better." Clark was my dad's favorite Byrd - at least until Gram Parsons joined. My dad always identified with the underdog - often a tragic underdog. Clark would only record one other album with the band, before embarking on a solo career that only saw success and acclaim after his passing. Clark was a great songwriter and - not playing an instrument himself - was the one who held the harmonies in the line.

Decades later, my favorites on this album are originals buried deep beneath the covers. I care little for their rendition of the title track when stacking it up against the others, and it is Dylan's original that holds resonance. My mom always preferred that version, most notably the line, "to dance beneath the diamond skies with one hand waving free." In 2003, I was working on a documentary film about my mom's brother, Steve, who'd committed suicide years before I was born. Her family had grown up in Michigan, but Steve had come to San Francisco in the sixties searching for something. As we strolled Haight Street and I filmed the scenery, we happened upon a street performer. I chatted with him briefly and he informed me that he played mostly Dylan songs. I asked him if I could film him playing his favorite. He agreed, and proceeded to sing "Mr. Tambourine Man." Though it was all by chance, that moment ended up becoming a defining point in the film. Even if I tried to escape them, the music that defined my life as a child continues to define it today.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)